By Coco Dolle

Mexico-based artist Domenico Zindato has long been situated within the histories of self-taught art. Born in southern Italy, Zindato lives in Cuernavaca, Mexico, where he has developed a visual language shaped by sustained movement between regions and traditions, a trajectory that informs the publication’s emphasis on Latin American artistic contexts.

Originally brought to wider attention by the pioneering New York dealer Phyllis Kind, Zindato has been represented by Andrew Edlin Gallery since 2009. Recently the gallery showcased his fifth solo exhibition. On that occasion, the artist was present signing and dedicating his new book during the opening event.

Zindato’s book "Domenico Zindato: On the Dotted Line" was published in 2025 and conceived and assembled by Aurélie Bernard Wortsman, and presents a focused account of an artist whose work moves across material, symbolic, and geographic terrains.

Combining Julián Sánchez González’s essay with an extensive interview conducted by Wortsman, the book brings critical interpretation together with the artist’s reflections on technique, influences, and material evolution.

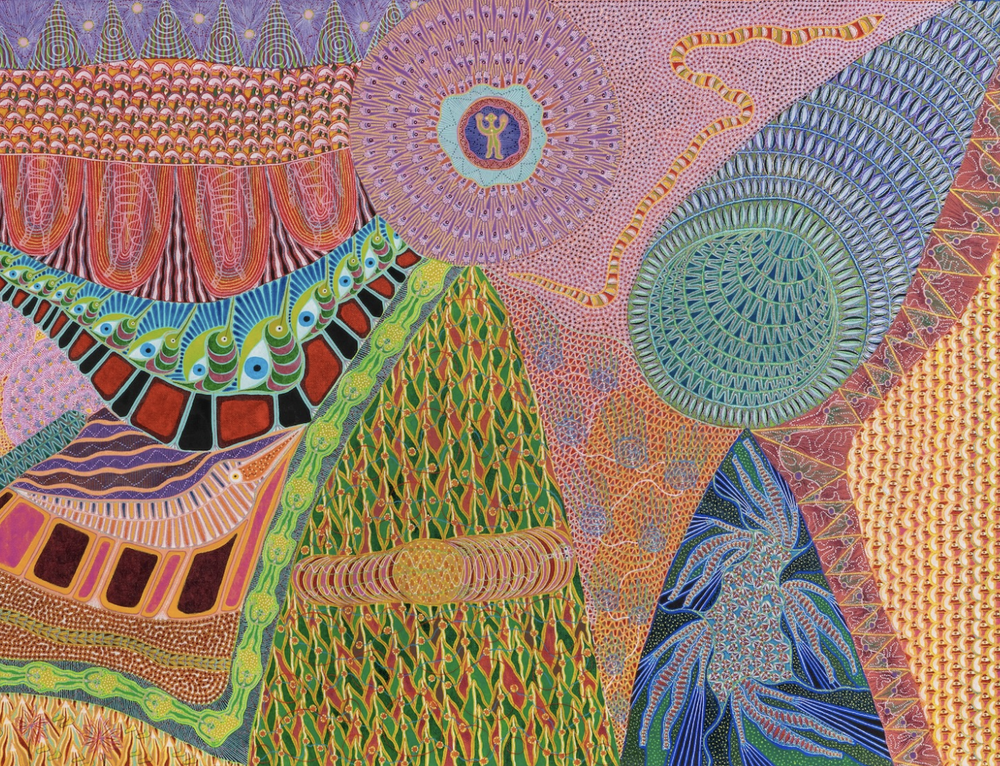

Sánchez González places Zindato within an international conversation on ritual, spirituality, and ecological thought, emphasizing themes of coexistence and interdependence that run throughout the artist’s three-decade trajectory. His compositions, densely layered with human, animal, and abstract forms, function as interconnected pictorial systems in which microcosmic and macrocosmic scales converge. Encounters with Indigenous visual traditions in Mexico, along with travels through the Amazon, provide important context for the essay’s reading of the work as an exploration of relational existence.

The publication broadens that framing, placing his work in closer relation to artistic developments across Latin America and to the visual cultures encountered during decades living in Mexico. At the same time, it acknowledges affinities with artists such as Emma Kunz and Augustin Lesage, figures associated with trance-based or mediumistic forms of image-making, while avoiding reductive categorization.

The interview expands this perspective by tracing the experiential foundations of the work. Zindato recalls formative periods spent in Berlin’s late-1980s music and performance scenes, experiences that shaped his interest in rhythm, collective experience, and altered states of perception. These influences, together with later engagements with ritual practices in Latin America, inform the tactile, process-oriented methods he describes.

A central focus of On the Dotted Line is the recent turn toward painting. Beginning with hand-rubbed pastel grounds and building through successive layers of ink, acrylic, and flashe, the new canvases extend earlier approaches developed on paper and leaves into broader chromatic fields and more immersive spatial environments. The plate section underscores this shift, presenting expansive compositions of spiraling lines, cellular forms, and constellations of dots alongside smaller works that maintain a more intimate scale.

By aligning essay, interview, and plates, the publication makes clear why Zindato’s recent paintings matter: they bring decades of accumulated imagery and technique into a more expansive pictorial register. The result is a book that presents painting, in Zindato’s hands, as both a material process and a means of mapping the interwoven relations that shape lived and imagined worlds.